“The Everything Shortage,” more commonly known as the Global Supply Chain Crisis – four words that have made a lot of headlines in recent news. You’ve probably been hearing a lot about it; empty shelves, soaring freight rates, and the biggest price inflations since 2008 have all been major talking points in world news.

What does it all mean? In short, the world is running out.

It’s running out of a wide variety of products. From cars to paint to equipment to electronics – if you need to gather the necessary parts or raw materials you need to assemble your product from different regions of the world, chances are your production is significantly hit, and you’re no longer able to produce as much, in time, or at all.

So what’s happening? What is this supply crisis? How bad is it? And why has it gotten this bad?

1. Demand Surge

If we’re to give you the full story here, we’ll want to trace it back to the beginning.

The story starts with the pandemic that disrupted most industries across the globe, COVID-19. At the end of Q2, we shared our last industry update through this blog post. Through it we highlighted how COVID has had its toll on the supply chain, and what that meant for shipping, and, consequently, trucking – allow us to recap.

When the pandemic first erupted, most people, and corporations, did not know what to make of it or the potential consequences it would have. In terms of the shipping industry, the preliminary assessment was that if an overwhelming pandemic is sending us into worldwide lockdowns, then the demand for shipping would definitely plummet. This assessment automatically led to the knee-jerk reaction of shipping lines cutting schedules, in anticipation of the demand drop.

While the entire supply chain, along with almost every other industry, did feel an initial setback on a global scale, things quickly turned up. As time progressed, with more and more time on their hands, and with less money, they could spend on services, due to the lockdowns, people started to shift significantly towards e-commerce – particularly in the U.S. as a result of the government-aided stimuli. People could no longer spend their money on cinemas, restaurants, or family vacations. Instead, adapting to the lockdown environment, people were buying everything they could to bring the outside world into their homes. Exercise equipment, home offices, and in-house entertainment consoles were all on the online shopping lists many people were then chasing.

With the majority of these goods flowing through the maritime market, which sat at an annual value of $14 trillion (2019), the demand for shipping significantly shot up – and it caught the industry by surprise. In comparison with pre-pandemic rates, the volume has risen by as much as 25%.

2. Container Shortages

While it was a welcomed surprise in terms of demand regeneration, it was not, by any means, business as usual. The surge in demand had caught the industry off-guard. A major enabler of the whole supply chain, the actual equipment (i.e. containers), was “misplaced”. Containers were not optimally positioned to deal with this newfound demand.

For example, China had sent out PPE (masks, medical supplies, and safety equipment) to various locations around the world, a lot of which had no commodities to ship back to China, resulting in the pile-up of much-needed containers at these locations. With demand so high on the actual container ships, there was little room for the repositioning of these containers, or the provision of equipment to meet the demand altogether.

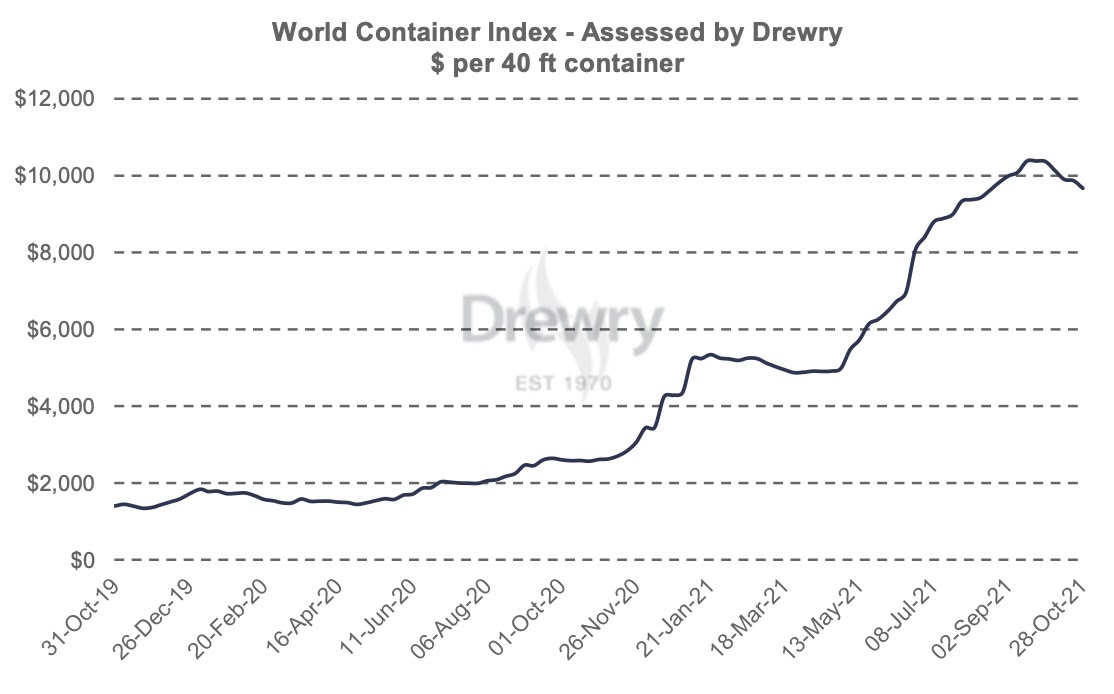

Compounding that with the surging demand for goods, containers suddenly became a scarce commodity themselves. And as the rules of economics dictate, high demand and scarce supply are a recipe for a price increase. The World Container Index (WCI), is a standardized average of what it costs to ship a 40-foot-container, in USD. Below is a graph that represents just how expensive it has become to ship that same exact 40-foot-container that was shipped pre-pandemic.

3. Port Congestion

To start off, it’s important to understand that the shipping industry operates in a “just-in-time” manner. The goal here is to be as lean as possible, you want your ships to arrive just-in-time so that they arrive when they’re scheduled to, not wait in line outside of the port to berth (park in its allotted area at the port), and only spend the necessary time required at berth for unloading. With that in mind, let’s get back to the story.

While it was acknowledged as the birthplace of the pandemic, China was one of the quickest countries to bounce back to its feet in terms of handling the virus and reviving its production. With the US still struggling with the virus, not only did local production take a big hit, but so too did the ports. Other than social distancing and other COVID-inflicted slowdowns, just like many offices we’ve seen get closed off for a while after a COVID case is found, ports were shut down on the back of dock workers getting sick as well. With nobody there to unload the ships, a major bottleneck was created. That bottleneck has had a growing impact on schedules, and we are still experiencing the effects to this day.

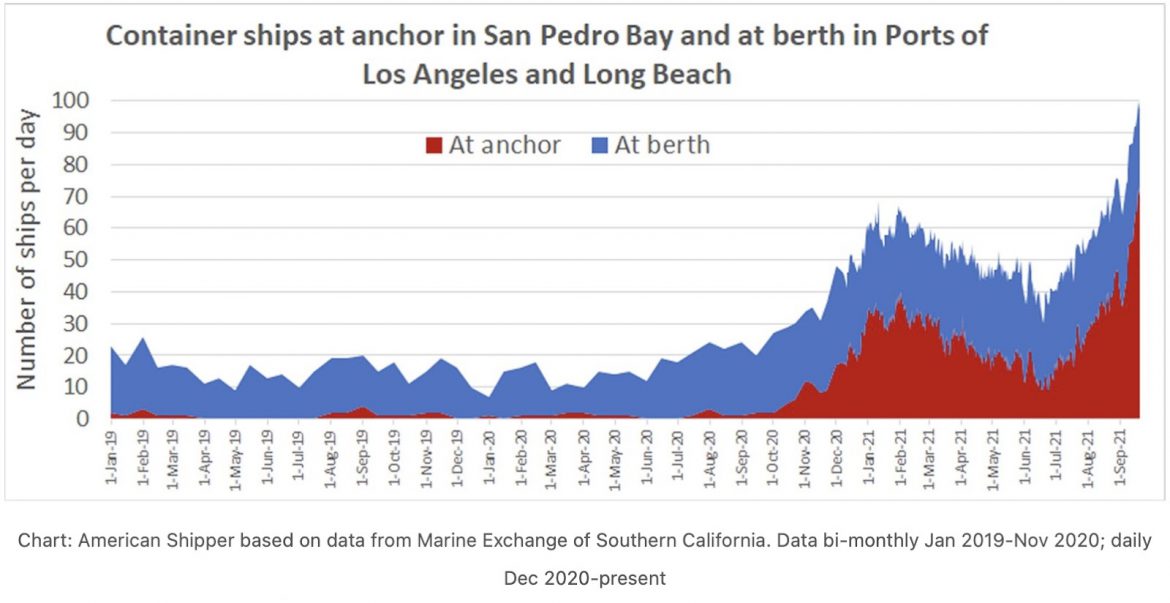

Ships started spending more time at berths (the dock they unload containers in), and, what’s worse, they spent significant time just anchored in the water waiting for their turns to get into the ports. For context, ships waiting in anchor for their turn at the port was not something that was common at all pre-pandemic. Today, we’re seeing more than 70 ships a day completely idle, waiting to unload containers at ports.

While average berth times were around 8 hours at dock back in 2019, this year we’re seeing berth times as high as 89 hours, with a total port waiting time reaching 14 days. That’s 14 days spent idly at sea, holding up ships, cargo space, and precious containers that are very much in demand elsewhere in the world. With the actual trip time being almost the same number of days from the Far East to the US, this means that it’s taking a single ship twice the amount of time to complete its normal route, again, holding up precious cargo space and containers that are needed elsewhere in the world.

Beyond these US west coast ports, Fortune reports more than 600 ships waiting to enter ports. Below are a few photos that show the unprecedented idleness of containerships

4. Truck Drivers

To further exacerbate the situation, there comes an extremely important piece of the supply chain puzzle, the truck drivers. Other than their supply-chain-enforced troubles such as the lack of parts or vinyl for their trucks, truck drivers in the US have been systematically opting out of the industry on the back of low pay and suboptimal working conditions. And that was before the pandemic. It’s not stemming from a lack of interest in the industry, it’s an extremely high turnover. Drivers opt-out when they become more familiar with the life and working conditions they’re committing to. In the pre-pandemic era, the shortage of truck drivers was reported to be around 60,000 drivers.

Today, at a time when ports are filled to the brim with containers and are in dire need of drivers to clear these containers out, the country is reporting a shortage of around 80,000 truck drivers, with the trend continuing on to 160,000 in deficit by 2030 unless serious changes are put in place. Moreover, the Financial Times has reported that those who are committing to the industry, in Europe as well, are approaching severe burnout, which will definitely further aggravate the global supply chain troubles we’re facing today.

Fixes in the US

The Biden administration has recently reacted to these challenges through several initiatives:

-

The state department will allot millions of dollars worth of grants and additional funding to provide Mexico and Central America with technical assistance to help alleviate the pressure on the supply chain, improving and simplifying processes at ports along the way to help facilitate effectively, and sustainable, solutions.

-

Biden has taken to the G-20 summit to address the challenges affecting the global supply chain, urging the involvement of the private sector to collaborate on clearing the backlog.

-

The Biden administration also issued an order for 24/7 operating hours at major American ports to help boost the clearing of the bottleneck. These ports allegedly operated only 16 hours a day, but have responded with statements that they’d already been working 24/7 and that working hours aren’t really the bottleneck here.

- The announcement of substantial fines on containers holding up space at ports incentivizes the early release of these containers from the ports. Effective November 1st, once a container is offloaded from a vessel, it counts 9 days of free time, after which $100 will be charged per container per day until that container is released. For rail-transport containers, the free time stands at 3 days.

While these are steps towards clearing the major bottleneck in the US that is significantly affecting the supply chain worldwide, many industry experts are still skeptical about the practicality of these solutions clearing the crisis in the near future. Today, these problems are expected to persist well into 2022, with some analysts estimating that it will still be in effect as late as Christmas 2022.

Ryan Petersen, CEO of Flexport, shared his thoughts on the bottlenecks and labor shortages in the US. The freight forwarding company had boots on the ground to observe what was happening firsthand, bringing in a taco food truck as a sort of thank you to the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), which represents the dockworkers at the US West Coast, who’ve been working around the clock to clear the container backlog at the Port of Long Beach.

They report that while the port is open 24/7, throughout the night they’ve only seen one truck come through. With minimal containers going out, there is minimal room for containers to come in, leaving the ships waiting for space to unload at the port, and keeping the cranes at the port idle.

Between equipment unavailability, and a shortage of truck drivers, there’s only so much the labor at the ports can do, and, as Ryan reports, they are doing a lot.

As a result of all these factors, there is a significant push from industry experts for people to shift towards domestic products, as now more than ever there grows the need to rely on as much self-sufficiency as possible, both to ease the strain on the supply chain and to actually allow consumers to actually get the products they’re looking to acquire.

So, how does that affect the region?

We’ve established that the crux of the issue is in the US, but how does that impact the region? Why is this, as industry experts are insisting, something of global impact, and not just a problem in the US?

First off, there’s a finite amount of ships and a finite amount of containers available to use for shipping. With the US holding a substantial portion of the containers either at the ports, or in ships outside of the ports, and with the hold up of the actual vessels as well, there’s a major capacity problem worldwide. There are fewer ships and containers to be utilized for the rest of the world.

Also, with longer wait times, and, hence, longer total trip times, a ship that fed the China-US West Coast route with commodities in 12 days is doing it in 24. That automatically has shipping lines significantly boost their freight rates, as we saw in the WCI chart above.

Moreover, while the global average was 600% price inflation, that inflation is not uniform. In our region, rates were more around 300% to 400%, with a lower absolute value freight rate in comparison with other more prominent trading routes, on the back of lower demand.

Now, what makes more business sense for these shipping lines: with a finite number of vessels and with some lanes significantly more profitable than others, which lanes would they send their ships to?

Exactly, they shifted ships, and containers, to routes that are more lucrative.

Tan Hua Joo

To give you more understanding of the dynamic here, shipping lines have been achieving absolutely record-breaking financial figures in 2021. Quarter after quarter, historical highs across the board.

We’ve already seen the effect of that happening, in the below chart you’ll see that only 50% of the ships that were supposed to serve the region, actually did. The rest? Redeployed to the main, more lucrative, east-west routes.

Additionally, these spikes in freight rates are always passed back to the consumer. As a result, we’re seeing price inflations in a lot of the products that rely on importing raw materials. And just like what’s happening in the US, the need to find alternatives, and sources locally, is rising across the region. A lot of countries simply cannot handle the surging cost of logistics, and have in turn started to look inward to some paths of self-sufficiency.

What’s the effect on Trella, and our shippers?

Particularly for those shippers whose commodities are valued at a relatively lower cost, shipping at these elevated prices simply did not make financial sense. The cost of logistics as a percentage of the total selling price grew too high for it to be worth shipping. As a result, we have seen shippers who have completely opted out, at least until more affordable ocean freight rates would become available to them.

Others who felt they could still operate at these rates, or who secured customers on the other end of the cycle who were willing to pay the surged logistical costs, still struggled to find space on ships or containers to ship their products to their destinations.

Part of our load cycle comprises tying in with shipping lines to allocate containers to specific bookings. On multitudes of occasions in the past few months, shippers that have actually booked containers to be exported on a ship send us these booking confirmations for us to start our trucking procedures, only for us to come back to them with responses from the shipping line that they are completely out of containers. We’ve had a lot of cancellations on the back of container availability, and our shippers communicate countless orders that never make it to us because they’re even notified of the lack of cargo space or containers well beforehand by the shipping lines.

To give another example, shippers usually ship from ports closest to their facilities to cut on trucking costs, provided the vessel on that port goes to the required destination. One of our biggest shippers in Egypt is located between Damietta and Port Said, at an average distance of 25 km from each port. As expected, that shipper did all of his trucking within that comfortable radius – up until the pandemic. Today, they’ve begun getting their empties from the Sokhna Port, 225 km away, at almost 4 times their normal trucking rate, because they simply cannot get their hands on empty containers.

As part of our dedication to our customers, we’ve been committing to finding solutions for them. Be it through the recommendation of shipping lines that might have gotten their hands on a batch of empties for the day, the direction of trucking from different ports, or the capitalizing on triangulated loads to make more use of the empty container resource, we’ve been able to provide our shippers with the solutions they need now more than ever.

On the back of our triangulation initiatives, we’ve been able to support shippers fulfill hundreds of loads despite the severe supply chain constraints we’ve all been dealt with.

To add more context here on the significantly lower numbers of containers to truck on import and export, shipping line volumes in Egypt, for example, have declined by as much as 35% MoM. This means that the actual ocean freight volumes available for trucking have declined by 35% MoM. The insights we’ve collected, as well as the reports within the region and worldwide, confirm that these figures are expected to extend well into next year and that it’s going to get worse before it gets better for the shipping industry.

1 comment

I want to to thank you for this fantastic read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it. I’ve got you book-marked to check out new things you post…